Several students have asked for recommended reading around their courses, so I’ve tried to put together a brief list of things worth reading; I’ve tried to divide the list into fairly serious reading, pop-economics, blogs and twitter – hopefully they’ll be useful. Read the rest of this page »

Latest

Definitions: The Market, “People Forces”, and “Free-People Principles”.

There are a few concepts in economics which seem to get us in trouble with non-economists, `the market’ and ‘utility’ being first among these. I’ll talk about utility another time, but here are some thoughts on the market.

As I (try to) teach my students, when economists talk about ‘the market’ we normally mean ‘people’. If you have a leak in your house you call a plumber to come and fix it. This is a fairly simple transaction, but how is value assigned to this? The plumber needs to eat, drink, and shelter his family, and knows approximately how many jobs like yours he is likely to get in a particular month. He also has an impression of how many other plumbers there are in the area, and he knows what else he could be doing with his time. This informs the minimum amount he will accept to do the job. Equally, you have a measure of how serious the leak is, how much damage it might cause, and hence have a maximum you are willing to pay for the plumber to come and fix it. Somewhere between these two points, depending on the relative balance of power between the two of you, will lie the price you pay. This is by no means the only way of assigning plumbers to people with leaks, but it’s quite smooth, and doesn’t require a third party. It’s also pretty good at providing enough plumbers – the more demand there is for plumbers, the higher the price a plumber can command, and so the more attractive plumbing becomes as a career path.

It might not seem very fair that this system inherently, explicitly, places higher value on one person’s time than another (which seems pretty illiberal), but the system doesn’t do that – nature does, and not just between people but within person. I enjoy my job, but I enjoy it a lot less between the hours of 2 and 3 AM. If you want me to work between those hours, I’ll want paying more than between 2 and 3 PM. The same is true of our plumber. At the same time, if you have a leak in the middle of the night, the maximum amount you’re willing to pay for prompt service by the plumber may also increase.

If you have a low income, or are otherwise liquidity constrained, you may be unable to afford a late night plumber, or indeed any plumber at all, at the prices commanded at the time. You might want to reach an agreement with your plumber, in advance of your needing him, whereby you pay him a small amount every month, in exchange for which he will fix your pipes if they ever break. This guaranteed income for the plumber reduces the risk for him, while knowing that you’ll never have a leak that you can’t to be fixed reduces your risk – both of you can sleep a little easier. If you’re confident in the quality of the plumber, and that he won’t renege should you ever develop a leak, everyone should be better off (or at least, nobody should be worse off).

Here, I’ve described a transaction in a market. What economists call the market has determine the price, and that price changes in response to the urgency of the situation – equivalent to a fall in supply (plumbers don’t like to work at night), and a rise in demand (you really need the pipe fixed). If you’re liquidity constrained, I’ve described how you might purchase a rudimentary insurance policy which is Pareto improving (at least one player is better off after the policy is been bought, and neither is worse off). We’ve also got a couple of conditions for this to work – you must know the plumber’s quality, and his commitment to honour the insurance policy must be credible enforceable. Without the first, you have an asymmetric information problem, and the market can fail. Without the second, you should (and probably will) choose not to buy insurance, but might instead save up the equivalent amount per month against a rainy day. Here, market failure is basically two people being unwilling or unable to reach an agreement because there is some obstacle (lack of information/contractibility). These obstacles might be solved through the intervention of a third party, such as the state.

Human interactions, human feelings, needs and wants, are what forms the scary-sounding market. When viewed through this lens, maybe economists don’t sound so crazy – when we say we’re putting our trust in the market, we really mean we’re putting our trust in people.

In case you were wondering, this is what a slippery slope looks like.

It’s always best to approach arguments about slippery slopes with some scepticism. These arguments are most commonly used by zealots to convince the agnostic that while the thing currently being proposed might not actually be bad, it will eventually and inevitably lead to the total collapse of human civilisation.

Gay marriage is fine, we don’t mind homosexuals, and some of our best friends are gay, but if you let them marry then it’s only a few steps from there to people marrying their sisters or pets.

ID cards aren’t a problem in themselves, but it’s a short walk from ID cards to Stalinist purges.

Jews are fine, and of course they should be able to own businesses, but if you don’t keep an eye on them then we’re only a few short years from living under the crushing yoke of Zionist oppression.

Bullshit.

Goings on in Cypress over the last few weeks, however, do look quite like a slippery slope. Part of this is down to the fact that we already seem to be slipping down it. Deposits in Eurozone banks are supposed to be insured up to 100,000 Euros, protecting depositors from risk, and in so doing preventing runs on banks. The announcement by the Cypriot government that they would be raiding those very same deposits in order to achieve goals set them by the EU, goes against the premise of a state backed guarantee on deposits. More scarily still, this was announced by the Cypriot government immediately after meetings with the EU – who must have known.

A portion of this has now been rowed back upon, but this is of small comfort – the decision, only blocked by the Cypriot legislature, was taken by the EU to renege. Jeroen Dijsselbloem, the Dutch Finance minister and head of the Eurogroup of Finance Ministers, appears to have now suggested that this kind of raid on depositors could become, far from the exceptional circumstance we were told it would be, the new model for bailing out countries in distress – we have already begun to slide.

Runs on Eurozone banks have largely been avoided thus far by maintaining a level of confidence in sovereign powers ability to honour their guarantees, or at least the EU’s willingness to honour them should they be unable. The posturing in Cypress, to avoid EU taxpayers bailing out Russian millionaires, has done serious damage to this confidence. More importantly, the reversal of policy so quickly, and the prolonged closure of Cypriot banks to force a deal through, preventing a run, surely provides an incentive for depositors to strike pre-emptively, and to start running in advance of true danger, which will in turn create a liquidity crisis among the banks (for a case study on how to manufacture a crisis out of thin air, see last year’s fuel crisis).

Serious people in Europe seem to think that Cypress doesn’t matter – that it is too small, at just 0.2% of Eurozone GDP, to cause a crisis. This is interesting, because the EU has chosen to reveal the extent to which it is willing to expropriate funds from depositors in a place which is, by their own admission, of limited importance. They have, and for very little gain, revealed their type. I worry that the only way from here may be down.

Israel, “The Jews” and Persuasion Bias

Following comments made by the Lib Dem MP, David Ward, in which he suggested that “the Jews” had failed to adequately learn from the holocaust, many people have weighed in to denounce him, particularly for the parallels he draws between the treatment of Jews by the Nazis, and the treatment of Palestinians by the Jews (his words, not mine).

Now, this blog is mainly about economics, and the behavioural stuff specifically (whatever that is), so I’m reluctant to wade into this kind of argument. My mind is, however, drawn to a paper by Ayca Giritligil and Co-Authors, on social influence and persuasion bias – essentially finding that because of people’s selective social groups, and the tendency for information to be repeated but discounted on secondary hearings, groups can tend towards a single, often extreme, view points, even in the presence of evidence which is balanced.

From my days as a young and idealistic undergrad (three words that can no longer be used to describe me, sadly), I remember student politics being dominated by a kind of pro-palestinian echo-chamber. The overwhelming majority of people felt sympathy for what they felt to be the underdog in the Arab-Israeli conflict, and didn’t come close to approaching antisemitism. A few of the louder, shriller voices, however, could be heard conflating Israel, and particularly the IDF, with Jews generally, and that is dangerous. I do not have many Jewish friends, but as far as I’m aware none of them have ever persecuted anyone, or annexed anything. Unfortunately, because these people are the loudest, and have the strongest held beliefs, others can be drawn, slowly and unconsciously, into sharing more and more of their views – something we should be very scared of, because that way madness lies.

As a salve, I offer up two pieces on the matter:

First, Daniel Finkelstein in the Times (behind a paywall): “Lessons form the holocaust? Try these two?”

Second, Hugo Rifkind in the Spectator: “Gerald Scarfe isn’t anti-semitic… but David Ward is“

Opposition to Gay Marriage and Psychology

The house of commons will vote next week on whether Gay Marriage should be allowed in the UK (in some places, if they want to, except churches, even if they do). Given that the measure is supported by the Prime Minister, by the Labour leadership, and by the Liberal Democrats, it can be expected to pass.

This is not to say that there will not be those who vote against it. MPs of what is called (by them) a `moral conservative’ inclination will vote against gay marriage, believing it to be evil, and just one step away form the state sanctioned marrying of people to farm animals. Let’s leave aside the ridiculousness here (as the Times’ Hugo Rifkind argued on twitter, two men having sex is already legal, having sex with animals is not), and the question this raises about my own identity (by being in favour of gay marriage but against a large state, does this make me an immoral conservative?), and focus on change.

Journalist and Former Tory MP Matthew Parris, in his column in today’s Times, reports on the interesting fact that Conservative MPs and Bishops who were previously against civil partnerships are now in favour of them, arguing that they are fantastic and that they negate the need for equal marriage for homosexuals.

While there is no doubt some fancy political footwork here (by arguing that civil partnerships are sufficient they weaken the case for gay marriage among the agnostic), Parris argues that in the main their opinion actually has changed since the civil partnership law was past, just as many tories in the 1960s who voted against the legalisation of homosexuality eventually came to support it. Society, after all, moves on. Yet these same people, who have seen society, and themselves, move past their prior convictions, believe that their new views about gay marriage are permanent.

This theory finds support in the work of Harvard’s Dan Gilbert and others. In their paper (an easier to access lay-report can be found here), they find that asking people to consider how they have changed over the last, say, 10 or 20 years, they believe that they have changed a great deal – regretting some of their past behaviours, and finding other embarrassing. Asked to look ahead to the future, and to say whether they expect to change over the next 10 or 20 years, they believe that they will not.Although fluid up to this point, from here on our their personalities and views will be completely fixed.

The consequences of this `end of history illusion’ as Gilbert et al call it are trivial when they mean that you invest too heavily in memorabilia for a band you won’t like in ten years. If what Parris describes is correct, the consequences may be far more serious – a loss of liberty for thousands of people.

Approximately 15 seconds of fame

Last night I was interviewed by ITV news west as part of their coverage of the Bristol Pound, a local currency for Bristol. As is the lot in life of economists, I’m cast as a naysayer in this debate (and not for the first time).

I don’t seem to be able to embed the video in this post, but it can be found here if anyone is interested (try not to blink or you’ll miss me).

Stick that in your pipe…

A couple of months ago I was giving a public talk on the use of Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) in public policy, and during the Q&A session at the end, a colleague suggested that I was `overselling’ – that there were a great many areas where RCTs cannot be used to test policy. I’ve heard this argument before and since, and I tend to agree – certainly things like macro policy would be nearly impossible to test, and there are important and large limitations to the use of RCTs in other areas as well. Particularly, I’m often told, the Labour market. Policies designed to get people back into work must be evaluated by ex-post methods, because an RCT would be impossible.

Imagine how pleased I am to see just such an RCT emerging from the government’s Behavioural Insights Team. Announced this weekend, the team has been testing interventions to help people get back into work in a jobcentre in Essex (details here), with encouraging results. Hopefully this is an important step for evidence based policy in this area.

Politics and Behavioural Economics

A couple of interesting stories in the last couple of days, both of which may have behavioural angles.

First, Nadine Dorries, conservative MP and anti-abortion activist, has decided to go on “I’m a celebrity, get me out of here”. The consensus so far is that she isn’t really a celebrity, but that most sane people would gladly get her out of here. Chris Dillow has blogged about behavioural biases at play in her decision. I’d also volunteer overconfidence as another possibility here – not in her ability to win I’m a celebrity, but in her ability to survive this politically – perhaps she believes that she is too vital an asset to her party to have the whip withdrawn, or to face a serious challenger from within the conservatives at the next election? The response of Sir George Young, the new Chief Whip, who has withdrawn her status as a Conservative MP, at least temporarily, strongly suggests that she was wrong. After attacking the Prime Minister and Chancellor for being arrogant posh boys and surviving, perhaps she believed this trend would continue (this is an example of the behavioural bias known as the Gambler’s fallacy). My personal view is that this constitutes evidence that Ms Dorries suffers from the Dunning-Kruger effect.

On the less entertaining but more practical side, Jodi Beggs reports the use of an interesting behavioural technique by the Obama campaign – telling people how many people with their first name have already voted. If only they’d run an RCT.

Some thoughts on a living wage

Mr Milliband is not currently in government, so he is at his leisure to promise this now and then renege and fudge his way out of it come the revolution (or rather, come his probable election in 2015), but let us assume for the time being that he is actually serious about legislating (as part of the 2016 Finance Bill, let’s assume), to ensure that people must be paid a living wage for their work.

The Evidence:

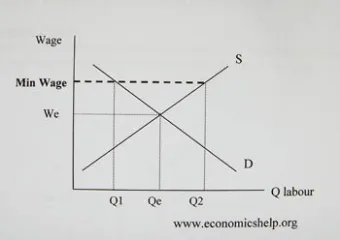

Traditional economic thought suggests that wage minima cause unemployment. The diagram below, shows that imposing a minimum wage moves forces the labour market off equilibrium, increasing the supply of labour (for more money, more people are willing to work), while at the same time decreasing the number of people actually employed (if labour is more expensive, less of it will be demanded by employers).

Card and Krueger’s (1994) paper offered a test of this theory, by comparing employment in New Jersey (where the minimum wage rose), to that in neighbouring Pennsylvania (where they did not), and found no evidence that employment, even of low-paid workers, was adversely affected by the rise. The UK instituted a minimum wage in 1998, considerably after the United States, and the evidence from here appears to be consistent with Card and Krueger’s findings – there was no massive spike in unemployment.

Things may now be changing, however. At the time of its introduction, the economy was doing well, and wages were generally on the rise. For the duration of Tony Blair’s government, the job market was constrained by the supply of labour, not demand for it – wages would naturally have been rising anyway, and so for very few lines of work was the minimum wage actually binding.

Now, things have changed. The economy has been lurching between anaemic growth and outright recession for four years, and unemployment is, naturally, much higher than before the financial crisis. Of particular concern is the number of NEETs (that is, people not in employment, education or training), particularly young NEETs. These have risen from 13% of young people at their nadir (2004), to 17% now (hat-tip to my colleagues Jack Britton and Lindsey Macmillan). Obviously has a lot to answer for here (these figures may conceal a larger rise in youth displacement, as many young people may have decided to stay in education longer in hope of riding out the recession), but it is now probably fair to say that the labour market has become much more of a buyer’s market. Combine this with the fall in productivity in the last few years, and we might expect the effect of a rise in minimum wages (particularly one of 20-30%), to lead to a fall in net employment – something that would certainly be bad for those affected.

Is there a behavioural angle to this, or are you just wasting our time?

First year micro will teach you that people are paid their marginal product of labour – that is to say, they are paid what they are worth, and exactly that. I do not believe that I go against most people’s experience of the world when I say that I find this model to be broadly nonsense. Assuming diminishing returns to a variable input (in this case labour), the more hours you work, the less you should get paid per hour. Instead, there is a rather more complex negotiating process at play, which typically favours the more powerful player – in the case of the current labour market, the employer.

Some models, such as Shapiro-Stiglitz (1984), predict that employees will be paid above their outside option (a combination of the value of some other job they might get and unemployment benefits), to induce effort. I allude vaguely to this model in my Erudition column this month, and it is this kind of logic (if I reduce the outside option by cutting benefits, more people will exert effort/be employed), that may be motivating the current government’s plans to curb benefits. Neither of these is really very behavioural.

There is another argument, however, which suggests that employees care not just about how much they are paid by their employer, but also the motivation behind that payment. Put a different way, a worker decides to exert effort (or not) above what is contractable, in response to the sense that their employer cares about them or is a decent person/organisation. If an employer pays the bare minimum, this suggests that they are concerned solely for their own profit and not for their employee’s welfare. If they pay a “living wage”, perhaps people will feel better about their employer and so work harder.

This idea of reciprocity is a behavioural characteristic, and was modelled by (among others), Armin Falk and Urs Fischbacher (2006), and there is a good amount of experimental evidence from the lab to suggest it’s existence, although some argue that it exists merely as an artefact of repeated play (this is a theoretical distinction and should make no substantive difference to outcomes). In some field settings, reciprocity has been seen to be a powerful way of inducing some behaviours, such as charitable giving.

In a labour context, however, the evidence is rather less optimistic. Uri Gneezy (2003), conducted a real effort experiment to test for the effect of paying people high wages on their productivity. He finds that while higher wages do induce a slightly higher level of productivity, whether or not this is worthwhile from the company’s perspective is rather more ambiguous. Where there is a low return to effort, it is not, but when returns on extra effort from the employee are high, the benefits can outweigh the costs of extra wages. I suspect that, unfortunately, there is a relatively low return on effort for many jobs that are currently paid between the minimum wage and the `living wage’. Even if it is, we might expect any reciprocity effect to be lessened if a living wage is mandated by legislation (although this does not appear to be the case for warm-glow responses to altruism).

To sum up…

There isn’t in principle anything wrong with the idea of paying people more money in order to help them survive, and perhaps a rise in the minimum wage is the way to achieve this. The current state of the labour market, and the weak behavioural evidence in support, suggest to me that the most keenly felt effects will be lost employment for many, dramatically reducing the positive societal impact of paying people more money. Having spent the weekend thinking quite a lot about the fate of Comet employees who look set to lose their jobs before Christmas as a result of the firm’s £35million loss this year, I cannot see how their fate would have been improved if the company had been paying many of them 30% more. On balance, it seems that government’s resources could be better spent either through the benefit system (perhaps returning housing benefits to the under 25’s), or in improving the quality of education and training available for young NEETs.

A return…

After an extended absence, I’m back in Bristol, which means people once again get my views shoved down their throat. After a change in management at Erudition, I’m back in the economics brief there; my columns can be found here:

Benefit Cuts are not the only option

I’ve also debated Dr Alistair Jacklin on the topic of whether or not the BBC is good for news coverage in the UK, and Susan Steed on whether or not local currencies are good thing (they aren’t), in response to the launch of the Bristol pound (on the CMPO Viewpoint Blog).

Hopefully more to follow.